Colosseum

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

The

Colosseum, or the

Coliseum, originally the

Flavian Amphitheatre (

Latin:

Amphitheatrum Flavium,

Italian Anfiteatro Flavio or

Colosseo), is an elliptical

amphitheatre in the centre of the city of

Rome,

Italy, the largest ever built in the

Roman Empire. It is considered one of the greatest works of

Roman architecture and

Roman engineering.

Occupying a site just east of the

Roman Forum, its construction started between 70 and 72 AD

[1] under the emperor

Vespasian and was completed in 80 AD under

Titus,

[2] with further modifications being made during

Domitian's reign (81–96).

[3] The name "

Amphitheatrum Flavium" derives from both Vespasian's and Titus's family name (

Flavius, from the

gens Flavia).

Capable of seating 50,000 spectators,

[1][4][5] the Colosseum was used for gladiatorial contests and public spectacles such as mock sea battles, animal hunts,

executions, re-enactments of famous battles, and dramas based on

Classical mythology. The building ceased to be used for entertainment in the

early medieval era. It was later reused for such purposes as housing, workshops, quarters for a religious order, a

fortress, a

quarry, and a

Christian shrine.

Although in the 21st century it stays partially ruined because of damage caused by devastating

earthquakes and stone-robbers, the Colosseum is an

iconic symbol of

Imperial Rome. It is one of Rome's most popular

tourist attractions and still has close connections with the

Roman Catholic Church, as each

Good Friday the

Pope leads a torchlit

"Way of the Cross" procession that starts in the area around the Colosseum.

[6]

The Colosseum is also depicted on the

Italian version of the

five-cent euro coin.

The Colosseum's original Latin name was

Amphitheatrum Flavium, often anglicized as

Flavian Amphitheater. The building was constructed by emperors of the

Flavian dynasty, hence its original name, after the reign of Emperor Nero.

[7] This name is still used in

modern English, but generally the structure is better known as the Colosseum. In antiquity, Romans may have referred to the Colosseum by the unofficial name

Amphitheatrum Caesareum; this name could have been strictly poetic.

[8][9] This name was not exclusive to the Colosseum; Vespasian and Titus, builders of the Colosseum, also constructed an

amphitheater of the same name in

Puteoli (modern Pozzuoli).

[10]

The name

Colosseum has long been believed to be derived from a

colossal statue of Nero nearby.

[3] This statue was later remodeled by

Nero's successors into the likeness of

Helios (

Sol) or

Apollo, the sun god, by adding the appropriate solar crown. Nero's head was also replaced several times with the heads of succeeding emperors. Despite its

pagan links, the statue remained standing well into the medieval era and was credited with

magical powers. It came to be seen as an iconic symbol of the permanence of Rome.

In the 8th century, a famous epigram attributed to the

Venerable Bede celebrated the symbolic significance of the statue in a prophecy that is variously quoted:

Quamdiu stat Colisæus, stat et Roma; quando cadet colisæus, cadet et Roma; quando cadet Roma, cadet et mundus ("as long as the Colossus stands, so shall Rome; when the Colossus falls, Rome shall fall; when Rome falls, so falls the world").

[11] This is often mistranslated to refer to the Colosseum rather than the Colossus (as in, for instance,

Byron's poem

Childe Harold's Pilgrimage). However, at the time that the Pseudo-Bede wrote, the

masculine noun coliseus was applied to the statue rather than to what was still known as the Flavian amphitheatre.

The Colossus did eventually fall, possibly being pulled down to reuse its

bronze. By the year 1000 the name "Colosseum" had been coined to refer to the amphitheatre. The statue itself was largely forgotten and only its base survives, situated between the Colosseum and the nearby

Temple of Venus and Roma.

[12]

The name further evolved to

Coliseum during the Middle Ages. In Italy, the amphitheatre is still known as

il Colosseo, and other

Romance languages have come to use similar forms such as

le Colisée (

French),

el Coliseo (

Spanish) and

o Coliseu (

Portuguese).

[edit] History

[edit] Ancient

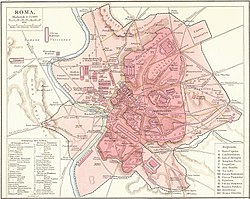

A map of central Rome during the Roman Empire, with the Colosseum at the upper right corner

Construction of the Colosseum began under the rule of the Emperor

Vespasian[3] in around 70–72AD. The site chosen was a flat area on the floor of a low valley between the

Caelian,

Esquiline and

Palatine Hills, through which a

canalised stream ran. By the 2nd century BC the area was densely inhabited. It was devastated by the

Great Fire of Rome in AD 64, following which

Nero seized much of the area to add to his personal domain. He built the grandiose

Domus Aurea on the site, in front of which he created an artificial lake surrounded by pavilions, gardens and porticoes. The existing

Aqua Claudia aqueduct was extended to supply water to the area and the gigantic bronze

Colossus of Nero was set up nearby at the entrance to the Domus Aurea.

[12]

Although the Colossus was preserved, much of the Domus Aurea was torn down. The lake was filled in and the land reused as the location for the new Flavian Amphitheatre. Gladiatorial schools and other support buildings were constructed nearby within the former grounds of the Domus Aurea. According to a reconstructed inscription found on the site, "the emperor Vespasian ordered this new amphitheatre to be erected from his general's share of the booty." This is thought to refer to the vast quantity of treasure seized by the Romans following their victory in the

Great Jewish Revolt in 70AD. The Colosseum can be thus interpreted as a great triumphal monument built in the Roman tradition of celebrating great victories

[12], placating the Roman people instead of returning soldiers. Vespasian's decision to build the Colosseum on the site of Nero's lake can also be seen as a populist gesture of returning to the people an area of the city which Nero had appropriated for his own use. In contrast to many other amphitheatres, which were located on the outskirts of a city, the Colosseum was constructed in the city centre; in effect, placing it both literally and symbolically at the heart of Rome.

The Colosseum had been completed up to the third story by the time of Vespasian's death in 79. The top level was finished and the building inaugurated by his son,

Titus, in 80.

[3] Dio Cassius recounts that over 9,000 wild animals were killed during the

inaugural games of the amphitheatre. The building was remodelled further under Vespasian's younger son, the newly designated Emperor

Domitian, who constructed the

hypogeum, a series of underground tunnels used to house animals and slaves. He also added a gallery to the top of the Colosseum to increase its

seating capacity.

In 217, the Colosseum was badly damaged by a major fire (caused by lightning, according to Dio Cassius

[13]) which destroyed the wooden upper levels of the amphitheatre's interior. It was not fully repaired until about 240 and underwent further repairs in 250 or 252 and again in 320. An inscription records the restoration of various parts of the Colosseum under

Theodosius II and

Valentinian III (reigned 425–455), possibly to repair damage caused by a major earthquake in 443; more work followed in 484

[14] and 508. The arena continued to be used for contests well into the 6th century, with gladiatorial fights last mentioned around 435. Animal hunts continued until at least 523, when

Anicius Maximus celebrated his consulship with some

venationes, criticised by King

Theodoric the Great for their high cost.

[12]

[edit] Medieval

Map of medieval Rome depicting the Colosseum

The Colosseum underwent several radical changes of use during the medieval period. By the late 6th century a small church had been built into the structure of the amphitheatre, though this apparently did not confer any particular religious significance on the building as a whole. The arena was converted into a cemetery. The numerous vaulted spaces in the arcades under the seating were converted into housing and workshops, and are recorded as still being rented out as late as the 12th century. Around 1200 the

Frangipani family took over the Colosseum and fortified it, apparently using it as a castle.

Severe damage was inflicted on the Colosseum by the great earthquake in 1349, causing the outer south side, lying on a less stable

alluvional terrain, to collapse. Much of the tumbled stone was reused to build palaces, churches, hospitals and other buildings elsewhere in Rome. A religious order moved into the northern third of the Colosseum in the mid-14th century and continued to inhabit it until as late as the early 19th century. The interior of the amphitheatre was extensively stripped of stone, which was reused elsewhere, or (in the case of the marble façade) was burned to make

quicklime.

[12] The bronze clamps which held the stonework together were pried or hacked out of the walls, leaving numerous pockmarks which still scar the building today.

[edit] Modern

Interior of the Colosseum, Rome.

Thomas Cole, 1832. Note the

Stations of the Cross around the arena and the extensive vegetation, both removed later in the 19th century.

During the 16th and 17th century, Church officials sought a productive role for the vast derelict hulk of the Colosseum.

Pope Sixtus V (1585–1590) planned to turn the building into a wool factory to provide employment for Rome's prostitutes, though this proposal fell through with his premature death.

[15] In 1671 Cardinal Altieri authorized its use for

bullfights; a public outcry caused the idea to be hastily abandoned.

The Colosseum in a 1757 engraving by Giovanni Battista Piranesi

In 1749,

Pope Benedict XIV endorsed as official Church policy the view that the Colosseum was a sacred site where early Christians had been

martyred. He forbade the use of the Colosseum as a quarry and consecrated the building to the

Passion of Christ and installed

Stations of the Cross, declaring it sanctified by the blood of the

Christian martyrs who perished there (

see Christians and the Colosseum). However there is no historical evidence to support Benedict's claim, nor is there even any evidence that anyone prior to the 16th century suggested this might be the case; the

Catholic Encyclopedia concludes that there are no historical grounds for the supposition. Later popes initiated various stabilization and restoration projects, removing the extensive vegetation which had overgrown the structure and threatened to damage it further. The façade was reinforced with triangular brick wedges in 1807 and 1827, and the interior was repaired in 1831, 1846 and in the 1930s. The arena substructure was partly excavated in 1810–1814 and 1874 and was fully exposed under

Benito Mussolini in the 1930s.

[12]

Between 1993 and 2000, parts of the outer wall were cleaned (left) to repair the Colosseum from automobile exhaust damage (right)

The Colosseum is today one of Rome's most popular tourist attractions, receiving millions of visitors annually. The effects of pollution and general deterioration over time prompted a major restoration programme carried out between 1993 and 2000, at a cost of 40 billion

Italian lire ($19.3m / €20.6m at 2000 prices). In recent years it has become a symbol of the international campaign against

capital punishment, which was abolished in Italy in 1948. Several anti–death penalty demonstrations took place in front of the Colosseum in 2000. Since that time, as a gesture against the death penalty, the local authorities of Rome change the color of the Colosseum's night time illumination from white to gold whenever a person condemned to the death penalty anywhere in the world gets their sentence commuted or is released,

[16] or if a jurisdiction abolishes the death penalty. Most recently, the Colosseum was illuminated in gold when capital punishment was abolished in the American state of

New Mexico in April 2009.

[17]

Today, the Colosseum is a background to the busy metropolis that is modern Rome.

Because of the ruined state of the interior, it is impractical to use the Colosseum to host large events; only a few hundred spectators can be accommodated in temporary seating. However, much larger concerts have been held just outside, using the Colosseum as a backdrop. Performers who have played at the Colosseum in recent years have included

Ray Charles (May 2002),

[18] Paul McCartney (May 2003),

[19] Elton John (September 2005),

[20] and

Billy Joel (July 2006).

[edit] Physical description

[edit] Exterior

The exterior of the Colosseum, showing the partially intact outer wall (

left) and the mostly intact inner wall (

right)

Original

façade of the Colosseum

Unlike earlier Greek theatres that were built into hillsides, the Colosseum is an entirely free-standing structure. It derives its basic exterior and interior architecture from that of two

Roman theatres back to back. It is elliptical in plan and is 189 meters (615 ft / 640 Roman feet) long, and 156 meters (510 ft / 528 Roman feet) wide, with a base area of 6 acres (24,000 m

2). The height of the outer wall is 48 meters (157 ft / 165 Roman feet). The perimeter originally measured 545 meters (1,788 ft / 1,835 Roman feet). The central arena is an oval 87 m (287 ft) long and 55 m (180 ft) wide, surrounded by a wall 5 m (15 ft) high, above which rose tiers of seating.

The outer wall is estimated to have required over 100,000 cubic meters (131,000

cu yd) of

travertine stone which were set without mortar held together by 300 tons of iron clamps.

[12] However, it has suffered extensive damage over the centuries, with large segments having collapsed following earthquakes. The north side of the perimeter wall is still standing; the distinctive triangular brick wedges at each end are modern additions, having been constructed in the early 19th century to shore up the wall. The remainder of the present-day exterior of the Colosseum is in fact the original interior wall.

The surviving part of the outer wall's monumental façade comprises three stories of superimposed

arcades surmounted by a

podium on which stands a tall

attic, both of which are pierced by windows interspersed at regular intervals. The arcades are framed by half-columns of the Tuscan,

Ionic, and

Corinthian orders, while the attic is decorated with Corinthian

pilasters.

[21] Each of the arches in the second- and third-floor arcades framed statues, probably honoring divinities and other figures from

Classical mythology.

Two hundred and forty mast

corbels were positioned around the top of the attic. They originally supported a retractable

awning, known as the

velarium, that kept the sun and rain off spectators. This consisted of a canvas-covered, net-like structure made of ropes, with a hole in the center.

[3] It covered two-thirds of the arena, and sloped down towards the center to catch the wind and provide a breeze for the audience. Sailors, specially enlisted from the Roman naval headquarters at

Misenum and housed in the nearby

Castra Misenatium, were used to work the

velarium.

[22]

The Colosseum's huge crowd capacity made it essential that the venue could be filled or evacuated quickly. Its architects adopted solutions very similar to those used in modern stadiums to deal with the same problem. The amphitheatre was ringed by eighty entrances at ground level, 76 of which were used by ordinary spectators.

[3] Each entrance and exit was numbered, as was each staircase. The northern main entrance was reserved for the

Roman Emperor and his aides, whilst the other three axial entrances were most likely used by the elite. All four axial entrances were richly decorated with painted

stucco reliefs, of which fragments survive. Many of the original outer entrances have disappeared with the collapse of the perimeter wall, but entrances XXIII (23) to LIV (54) still survive.

[12]

Spectators were given tickets in the form of numbered pottery shards, which directed them to the appropriate section and row. They accessed their seats via

vomitoria (singular

vomitorium), passageways that opened into a tier of seats from below or behind. These quickly dispersed people into their seats and, upon conclusion of the event or in an emergency evacuation, could permit their exit within only a few minutes. The name

vomitoria derived from the Latin word for a rapid discharge, from which

English derives the word

vomit.

[edit] Interior seating

Side view of Colosseum seating

According to the

Codex-Calendar of 354, the Colosseum could accommodate 87,000 people, although modern estimates put the figure at around 50,000. They were seated in a tiered arrangement that reflected the rigidly stratified nature of Roman society. Special boxes were provided at the north and south ends respectively for the Emperor and the

Vestal Virgins, providing the best views of the arena. Flanking them at the same level was a broad platform or

podium for the

senatorial class, who were allowed to bring their own chairs. The names of some 5th century senators can still be seen carved into the stonework, presumably reserving areas for their use.

The tier above the senators, known as the

maenianum primum, was occupied by the non-senatorial noble class or knights (

equites). The next level up, the

maenianum secundum, was originally reserved for ordinary Roman citizens (

plebians) and was divided into two sections. The lower part (the

immum) was for wealthy citizens, while the upper part (the

summum) was for poor citizens. Specific sectors were provided for other social groups: for instance, boys with their tutors, soldiers on leave, foreign dignitaries, scribes, heralds, priests and so on. Stone (and later marble) seating was provided for the citizens and nobles, who presumably would have brought their own cushions with them. Inscriptions identified the areas reserved for specific groups.

Another level, the

maenianum secundum in legneis, was added at the very top of the building during the reign of

Domitian. This comprised a gallery for the common poor,

slaves and women. It would have been either standing room only, or would have had very steep wooden benches. Some groups were banned altogether from the Colosseum, notably gravediggers, actors and former gladiators.

[12]

Each tier was divided into sections (

maeniana) by curved passages and low walls (

praecinctiones or

baltei), and were subdivided into

cunei, or wedges, by the steps and aisles from the vomitoria. Each row (

gradus) of seats was numbered, permitting each individual seat to be exactly designated by its gradus, cuneus, and number.

[23]

[edit] Arena and hypogeum

The Colosseum arena, showing the

hypogeum. The wooden walkway is a modern structure.

The arena itself was 83 meters by 48 meters (272 ft by 157 ft / 280 by 163 Roman feet).

[12] It comprised a wooden floor covered by sand (the Latin word for sand is

harena or

arena), covering an elaborate underground structure called the

hypogeum (literally meaning "underground"). Little now remains of the original arena floor, but the

hypogeum is still clearly visible. It consisted of a two-level subterranean network of tunnels and cages beneath the arena where gladiators and animals were held before contests began. Eighty vertical shafts provided instant access to the arena for caged animals and scenery pieces concealed underneath; larger hinged platforms, called

hegmata, provided access for elephants and the like. It was restructured on numerous occasions; at least twelve different phases of construction can be seen.

[12]

The

hypogeum was connected by underground tunnels to a number of points outside the Colosseum. Animals and performers were brought through the tunnel from nearby stables, with the gladiators' barracks at the

Ludus Magnus to the east also being connected by tunnels. Separate tunnels were provided for the Emperor and the Vestal Virgins to permit them to enter and exit the Colosseum without needing to pass through the crowds.

[12]

Substantial quantities of machinery also existed in the

hypogeum. Elevators and pulleys raised and lowered scenery and props, as well as lifting caged animals to the surface for release. There is evidence for the existence of major

hydraulic mechanisms

[12] and according to ancient accounts, it was possible to flood the arena rapidly, presumably via a connection to a nearby aqueduct.

[edit] Supporting buildings

The Colosseum and its activities supported a substantial industry in the area. In addition to the amphitheatre itself, many other buildings nearby were linked to the games. Immediately to the east is the remains of the

Ludus Magnus, a training school for gladiators. This was connected to the Colosseum by an underground passage, to allow easy access for the gladiators. The

Ludus Magnus had its own miniature training arena, which was itself a popular attraction for Roman spectators. Other training schools were in the same area, including the

Ludus Matutinus (Morning School), where fighters of animals were trained, plus the Dacian and Gallic Schools.

Also nearby were the

Armamentarium, comprising an armory to store weapons; the

Summum Choragium, where machinery was stored; the

Sanitarium, which had facilities to treat wounded gladiators; and the

Spoliarium, where bodies of dead gladiators were stripped of their armor and disposed of.

Around the perimeter of the Colosseum, at a distance of 18 m (59 ft) from the perimeter, was a series of tall stone posts, with five remaining on the eastern side. Various explanations have been advanced for their presence; they may have been a religious boundary, or an outer boundary for ticket checks, or an anchor for the

velarium or awning.

[12]

Right next to the Colosseum is also the

Arch of Constantine.

The Colosseum was used to host

gladiatorial shows as well as a variety of other events. The shows, called

munera, were always given by private individuals rather than the state. They had a strong religious element but were also demonstrations of power and family prestige, and were immensely popular with the population. Another popular type of show was the animal hunt, or

venatio. This utilized a great variety of wild beasts, mainly imported from

Africa and the

Middle East, and included creatures such as

rhinoceros,

hippopotamuses,

elephants,

giraffes,

aurochs,

wisents,

barbary lions,

panthers,

leopards,

bears,

caspian tigers,

crocodiles and

ostriches. Battles and hunts were often staged amid elaborate sets with movable trees and buildings. Such events were occasionally on a huge scale;

Trajan is said to have celebrated his victories in

Dacia in 107 with contests involving 11,000 animals and 10,000 gladiators over the course of 123 days.

During the early days of the Colosseum, ancient writers recorded that the building was used for

naumachiae (more properly known as

navalia proelia) or simulated sea battles. Accounts of the inaugural games held by Titus in AD 80 describe it being filled with water for a display of specially trained swimming horses and bulls. There is also an account of a re-enactment of a famous sea battle between the

Corcyrean (Corfiot) Greeks and the

Corinthians. This has been the subject of some debate among historians; although providing the water would not have been a problem, it is unclear how the arena could have been waterproofed, nor would there have been enough space in the arena for the warships to move around. It has been suggested that the reports either have the location wrong, or that the Colosseum originally featured a wide floodable channel down its central axis (which would later have been replaced by the hypogeum).

[12]

Sylvae or recreations of natural scenes were also held in the arena. Painters, technicians and architects would construct a simulation of a forest with real trees and bushes planted in the arena's floor. Animals would be introduced to populate the scene for the delight of the crowd. Such scenes might be used simply to display a natural environment for the urban population, or could otherwise be used as the backdrop for hunts or dramas depicting episodes from mythology. They were also occasionally used for executions in which the hero of the story — played by a condemned person — was killed in one of various gruesome but mythologically authentic ways, such as being mauled by beasts or burned to death.

The Colosseum today is now a major tourist attraction in Rome with thousands of tourists each year paying to view the interior arena, though entrance for EU citizens is partially subsidised, and under-18 and over-65 EU citizens' entrances are free.

[24] There is now a museum dedicated to

Eros located in the upper floor of the outer wall of the building. Part of the arena floor has been re-floored. Beneath the Colosseum, a network of subterranean passageways once used to transport wild animals and gladiators to the arena opened to the public in summer 2010.

[25]

The Colosseum is also the site of

Roman Catholic ceremonies in the 20th and 21st centuries. For instance,

Pope Benedict XVI leads the

Stations of the Cross called the

Scriptural Way of the Cross (which calls for more meditation) at the Colosseum

[26][27] on

Good Fridays.

[6]

A panorama of the interior of the Colosseum as it stands now.

[edit] Christians and the Colosseum

In the Middle Ages, the Colosseum was clearly not regarded as a sacred site. Its use as a fortress and then a quarry demonstrates how little spiritual importance was attached to it, at a time when sites associated with martyrs were highly venerated. It was not included in the itineraries compiled for the use of pilgrims nor in works such as the 12th century

Mirabilia Urbis Romae ("Marvels of the City of Rome"), which claims the

Circus Flaminius — but not the Colosseum — as the site of martyrdoms. Part of the structure was inhabited by a Christian order, but apparently not for any particular religious reason.

It appears to have been only in the 16th and 17th centuries that the Colosseum came to be regarded as a Christian site.

Pope Pius V (1566–1572) is said to have recommended that pilgrims gather sand from the arena of the Colosseum to serve as a relic, on the grounds that it was impregnated with the blood of martyrs. This seems to have been a minority view until it was popularised nearly a century later by

Fioravante Martinelli, who listed the Colosseum at the head of a list of places sacred to the martyrs in his 1653 book

Roma ex ethnica sacra.

Martinelli's book evidently had an effect on public opinion; in response to Cardinal Altieri's proposal some years later to turn the Colosseum into a bullring, Carlo Tomassi published a pamphlet in protest against what he regarded as an act of desecration. The ensuing controversy persuaded

Pope Clement X to close the Colosseum's external arcades and declare it a sanctuary, though quarrying continued for some time.

At the instance of St.

Leonard of Port Maurice, Pope

Benedict XIV (1740–1758) forbade the quarrying of the Colosseum and erected

Stations of the Cross around the arena, which remained until February 1874. St.

Benedict Joseph Labre spent the later years of his life within the walls of the Colosseum, living on

alms, prior to his death in 1783. Several 19th century popes funded repair and restoration work on the Colosseum, and it still retains a Christian connection today. Crosses stand in several points around the arena and every

Good Friday the Pope leads a

Via Crucis procession to the amphitheatre.

Plants on the inner walls of the Colosseum

The Colosseum has a wide and well-documented history of

flora ever since

Domenico Panaroli made the first catalogue of its plants in 1643. Since then, 684 species have been identified there. The peak was in 1855 (420 species). Attempts were made in 1871 to eradicate the vegetation, because of concerns over the damage that was being caused to the masonry, but much of it has returned.

[12] 242 species have been counted today and of the species first identified by Panaroli, 200 remain.

The variation of plants can be explained by the change of climate in Rome through the centuries. Additionally,

bird migration, flower blooming, and the growth of Rome that caused the Colosseum to become embedded within the modern city centre rather than on the outskirts of the ancient city, as well as deliberate transport of species, are also contributing causes. One other romantic reason often given is their seeds being unwittingly transported on the animals brought there from all corners of the empire.

[edit] Appearances in media

The iconic status of the Colosseum has led it to be featured in numerous films and other items of popular culture:

- Cole Porter's song "You're the Top" from the musical Anything Goes (1934) includes the line "You're the Top, You're the Coliseum".

- In the 1953 film Roman Holiday, the Colosseum famously serves as the backdrop for several scenes.

- In the 1954 film Demetrius and the Gladiators, the Emperor Caligula anachronistically sentences the Christian Demetrius to fight in the Colosseum.

- The conclusion of the 1957 film 20 Million Miles to Earth takes place at the Colosseum.

- In the 1972 film Way of the Dragon, Bruce Lee fought Chuck Norris in the Colosseum.

- In 1998 the Colosseum becomes a featured Santa Cam location for the annual NORAD Tracks Santa tracking effort.[28]

- In Ridley Scott's 2000 film Gladiator, the Colosseum was re-created via computer-generated imagery (CGI) to "restore" it to the glory of its heyday in the 2nd century. The depiction of the building itself is generally accurate and it gives a good impression of what the underground hypogeum would have been like.[citation needed]

- In the 2003 science fiction film The Core, a huge lightning superstorm destroys buildings and streets in Rome, culminating in the destruction of the Colosseum.

- In 2003, the Colosseum appeared in the video game Mario Kart: Double Dash!!, with the race track Wario Colosseum located in the building.

- In 2004, the remaining girls of America's Next Top Model, Cycle 2 did a photoshoot in the Colosseum for Solstice Sunglasses.

- In the 2008 film Jumper, the Colosseum was used as the location for one of the battles between the jumpers and the paladins.

- In the 2010 upcoming Ubisoft game, Assassin's Creed: Brotherhood. The player will be able to use the Colosseum as their base.

The Colosseum's fame as an entertainment venue has also led the name to be re-used for modern entertainment facilities, particularly in the United States, where theatres,

music halls and large buildings used for sport or exhibitions have commonly been called Colosseums or Coliseums.

[29]

[edit] References

The Colosseum from Colle Oppio gardens

[edit] Bibliography

- ^ a b Rome-accom.com, The full history of the Colosseum

- ^ BBC.co.uk, BBC's History of the Colosseum p. 2.

- ^ a b c d e f Roth, Leland M. (1993). Understanding Architecture: Its Elements, History and Meaning (First ed.). Boulder, CO: Westview Press. ISBN 0-06-430158-3.

- ^ William H. Byrnes IV (Spring 2005) "Ancient Roman Munificence: The Development of the Practice and Law of Charity". Rutgers Law Review vol. 57, issue 3, pp. 1043–1110.

- ^ BBC.co.uk, BBC's History of the Colosseum p. 1.

- ^ a b "Frommer's Events - Event Guide: Good Friday Procession in Rome (Palatine Hill, Italy)". Frommer's. http://events.frommers.com/sisp/index.htm?fx=event&event_id=11442. Retrieved 2008-04-08.

- ^ Willy Logan. "The Flavian Dynasty". http://www.wilhelmaerospace.org/Architecture/rome/colosseum/colosseum.html#flavius. Retrieved 2007-09-25.

- ^ J. C. Edmondson; Steve Mason, J. B. Rives (2005). Flavius Josephus and Flavian Rome. Oxford University Press. pp. 114.

- ^ "The Colosseum - History 1". http://www.the-colosseum.net/history/h1.htm. Retrieved 2008-01-26.

- ^ Mairui, Amedeo. Studi e ricerche sull'Anfiteatro Flavio Puteolano. Napoli : G. Macchiaroli, 1955. (OCLC 2078742)

- ^ "The Coliseum". The Catholic Encyclopedia. New Advent. http://www.newadvent.org/cathen/04101b.htm. Retrieved August 2, 2006. ; the form quoted from the Pseudo-Bede is that printed in Migne, Pat. Lat 94 (Paris, 1862:543, noted in F. Schneider, Rom und Romgedanke im Mittelalter (Munich) 1926:66f, 251, and in Roberto Weiss, The Renaissance Discovery of Classical Antiquity (Oxford:Blackwell) 1973:8 and note 5.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p Claridge, Amanda (1998). Rome: An Oxford Archaeological Guide (First ed.). Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press, 1998. pp. 276–282. ISBN 0-19-288003-9.

- ^ Cass. Dio lxxviii.25.

- ^ The repairs of the damages inflicted by the earthquake of 484 were paid for by the Consul Decius Marius Venantius Basilius, who put two inscriptions to celebrate his works (CIL VI, 1716).

- ^ "Rome." Encyclopædia Britannica. 2006.

- ^ Young, Gayle (2000-02-24). "On Italy's passionate opposition to death penalty". CNN.com (CNN). http://edition.cnn.com/SPECIALS/views/y/2000/02/young.italydeath.feb24/. Retrieved 2006-08-02.

- ^ Google.com

- ^ Colosseum stages peace concert, BBC News Online, 12 May 2002.

- ^ McCartney rocks the Colosseum, BBC News Online, 12 May 2003.

- ^ Sir Elton's free gig thrills Rome, BBC News Online, 4 September 2005.

- ^ Ian Archibald Richmond, Donald Emrys Strong, Janet DeLaine. "Colosseum", The Oxford Companion to Classical Civilization. Ed. Simon Hornblower and Antony Spawforth. Oxford University Press, 1998.

- ^ Downey, Charles T. (February 9, 2005). "The Colosseum Was a Skydome?". http://ionarts.blogspot.com/2005/02/colosseum-was-skydome.html. Retrieved 2006-08-02.

- ^ Samuel Ball Platner (as completed and revised by Thomas Ashby), A Topographical Dictionary of Ancient Rome. Oxford University Press, 1929.

- ^ The Colosseum.net : The resourceful site on the Colosseum.

- ^ Colosseum to open gladiator passageways for first time

- ^ Joseph M Champlin, The Stations of the Cross With Pope John Paul II Liguori Publications, 1994, ISBN 0-89243-679-4.

- ^ Vatican Description of the Stations of the Cross at the Colosseum: Pcf.va

- ^ NORAD Tracks Santa - Dec 2009 - Rome, Italy - English from YouTube

- ^ "Coliseum". Pocket Fowler's Modern English Usage. Ed. Robert Allen. Oxford University Press, 1999.

[edit] External links